Home » Methods for Calculating PI Compensation: Pros and Cons

Methods for Calculating PI Compensation: Pros and Cons

October 25, 2021

This is the second in a four-part CenterWatch Weekly series on the principles and best practices of setting investigator compensation levels that are both fair and compliant with federal laws. This week, we look at various methodologies for determining compensation.

There are several different methodologies, broadly speaking, for calculating principal investigator (PI) compensation, but within each one there is also room to customize certain elements to fit the particular needs of your organization.

Some methodologies rely on a more or less fixed fee, while others attempt to calculate the actual time and effort put into research activities by the PI, either estimating that time and effort in advance or charting it in real time as the study progresses. There are some obvious pros and cons to each approach.

The Research Salary Model

One method for paying a PI is to have compensation built into his or her salary. This model used to be the most common method for compensating study PIs, but it has fallen out of favor in recent years, according to Geoffrey Schick, director of site strategy partnerships at WCG. It often works best, he says, for large academic medical centers or organizations with relatively deep pockets for research.

There are advantages to this model, however. One is its relative ease. Once a fixed rate is determined, it requires no additional calculations. It can also help prioritize research and set clear expectations around how much of a physician’s time should be spent on research-related activities.

Schick provides the following example: A physician on staff at a large teaching hospital connected to a university may have $60,000 of her annual salary earmarked for teaching undergraduate and graduate classes, another $100,000 tied to her clinical work with the hospital’s patients and another $25,000 designated for research.

“We don’t tend to see this as much anymore, but that’s the old model,” Schick says. “The physician would negotiate a research salary and any additional studies beyond that initial expectation would be factored into the next year’s salary negotiations.”

But the research salary method can be a risky proposition, he says. If the volume of work for the PI decreases, the organization could end up paying too much on a per-hour basis. Conversely, if the volume of the PI’s work goes up, the physician may feel that he or she is not being compensated enough. The site would also need to do some work to show that the rate of pay was within a fair market value range. So, even if you wouldn’t be required to do as much upfront work to calculate a pay rate, you may have to do more work on the back end to justify it — and to document that justification.

The Percentage-of-Study-Budget Model

The percentage-of-study-budget method is essentially what it sounds like: PI reimbursement is calculated as a percentage of the final study budget. One advantage of this model is that, like the research salary model, compensation for the PI is easy to calculate. Unlike the research salary model, however, risk is being shared by the PI and the site since the payment will always be in proportion to the overall study budget. Also, like the research salary method, the percentage-based model requires very little in the way of administrative tracking.

One risk of this model, however, is that even though it’s tied to the overall study budget, the amount paid could still be disproportionate, in one direction or the other, to the actual work done by the PI in a given study. It can also get complicated in a study with multiple sub-investigators or with multiple protocol amendments due to the timing of when patients enroll. And if the study’s original PI has to be replaced, it can become problematic since expenses are often front-loaded and the original PI could have already received the bulk of the pay allotted for the full study.

Models Based on Time and Effort

For sites that are willing to do the work of tracking a PI’s time and effort, an hourly rate can be calculated that will set investigator compensation based on either estimated or actual work.

For a payment method using estimated time and effort, that work would be mapped out before the study begins. For instance, you may know that a necessary physical exam for a study should take about 30 minutes per patient or that the informed consent process should take roughly an hour. These estimates can be tallied up and presented in detail to the PI prior to the study. This method requires less paperwork from the PI than an accounting of actual time and effort, and it shows that real thought was put into reimbursement by the research team.

In a model based on actual time and effort, the PI would fill out documentation of the actual work performed during the trial, logging procedures and clinical services as well as administrative work. One advantage to this model is that it’s perhaps the most compliant from a regulatory and legal standpoint. So long as you can show that the agreed-upon hourly rate is based on fair market value, then the rest of the reimbursement model will be meticulously documented. On the other hand, the PI may bristle at the additional work required of real-time documentation, although templates provided by the site can ease some of that burden.

With the actual-time-and-effort model, a robust tracking mechanism is needed to make sure payments are made properly. There are also some inherent limits to a purely hourly rate of compensation. Some work, after all, is more difficult and those degrees of difficulty may also vary quite a bit from one study to another. On the plus side, having a PI document his or her work accurately can provide the site with really useful data that can be applied to future study budgeting.

According to Schick, the time-and-effort model fits better with some study tasks than with others. An hourly rate can be great for compensating for administrative work: meetings, reviewing reports or participating in conference calls, for instance. A model that captures the actual work done, in particular, can be a good way to make sure administrative work is fairly compensated. Often, tasks like reviewing inclusion and exclusion criteria for a study or reviewing patient medical profiles will fall to the study coordinator rather than the PI. But for smaller sites without much administrative support, that work can often land on the shoulders of the investigator. In other cases, an investigator might step in to do some of that work in a way that wasn’t planned. “If that’s the case, we want to make sure we’re capturing the time and effort the investigator is spending there and be able to move some of the dollars paid by the sponsor to compensate that work,” Schick says.

On the other hand, the time-and-effort model can be more difficult for patient interactions and clinical work, Schick says. “It’s just not nearly as conducive to that, since time isn’t always the most reliable marker of how much a given procedure or patient visit is worth monetarily.”

The Research RVU Method

Another model for investigator compensation hinges on what’s known as relative value units, or RVUs. At its most basic, the idea is that a number of RVUs could be assigned to a given task based on a combination of factors: for example, degree of difficulty, time and effort required to complete the task, and training or expertise required to perform the task. That number would then be multiplied by a standard coefficient and the result would be the reimbursement the PI would receive for the task.

This model has its roots in the Medicare program, which uses an RVU methodology to set reimbursement levels for covered procedures and services. Medicare assigns a current procedural terminology (CPT) code for all costs it will cover. A similar process is used by private insurers.

For PI compensation, RVUs would work in a similar way and are particularly useful for setting reimbursement for clinical services, “basically, anything with a CPT code,” Schick says.

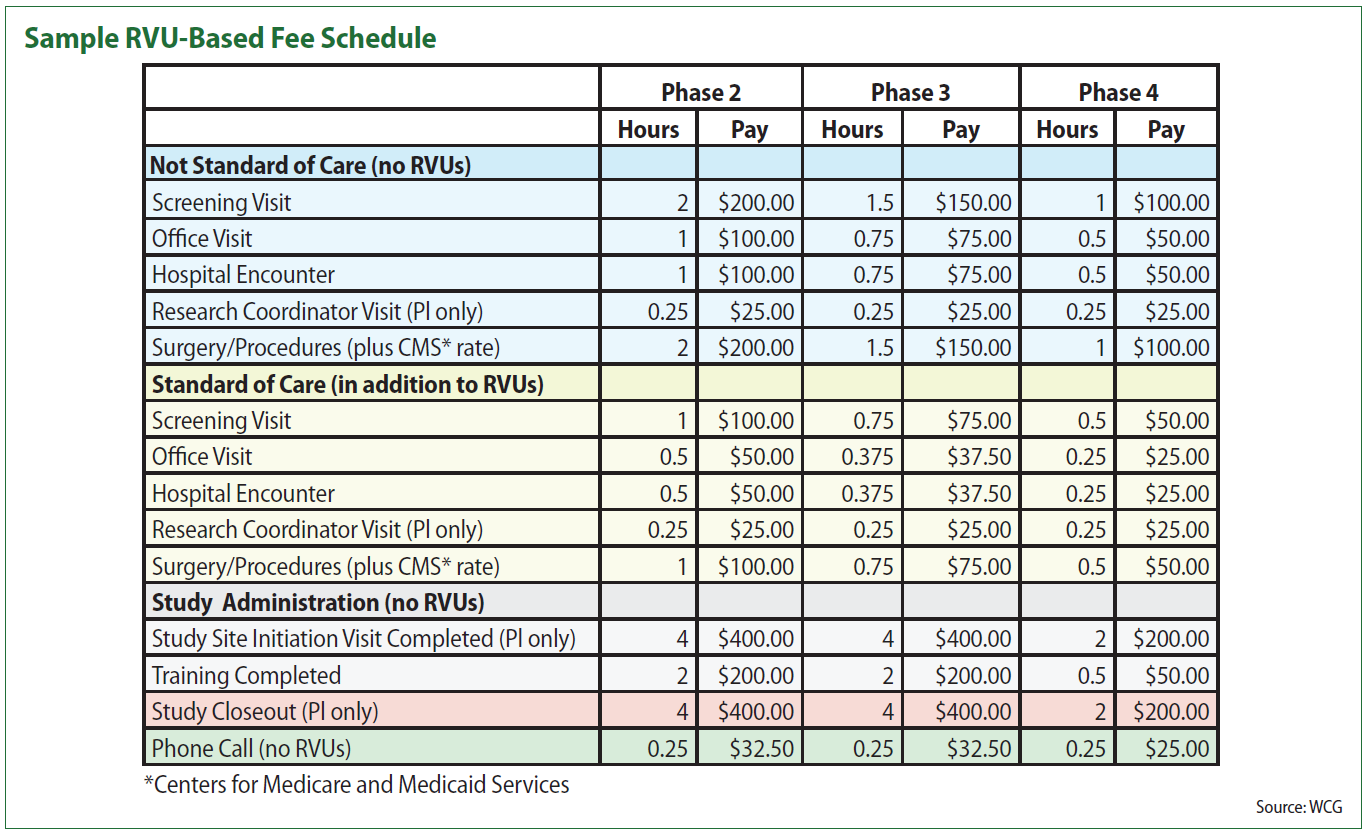

In the table, items highlighted in blue are those that are generally research-specific and paid for by research funds. The rows in yellow represent services that are performed as standard of care. The gray and pink items are administrative tasks that a PI may at times be asked to perform. The chart also differentiates based on the complexity of a research study, with different RVU levels — and thus different levels of compensation — for a phase 2, phase 3 and phase 4 study. “For device trials, those obviously don’t fit quite so neatly into those phases, but you could create correlatives based on the nature of the device study,” Schick suggests. A postmarket approval study, for instance, would generally align with a phase 4 trial for a pharmaceutical product.

The RVU model tends to work best, Schick says, to compensate for clinical services. “Whether it’s a blood draw, an office visit, the interpretation of an EKG or imaging scans: anything that’s associated with a CPT code. Because those are going to generate revenue based on a fee schedule that goes along with the code.” That revenue is then translated into research compensation. For some sites, that will be a monthly payment, Schick says, while other sites may choose to pay quarterly.

Within that RVU model, there’s still the question of how to set compensation to ensure it’s in the range of fair market value so that it doesn’t run afoul of any of the pertinent laws or regulations. Schick offers a few suggestions for setting that reimbursement level. One is to look at your peers in the industry, he says. “If you are looking at medical procedures or clinical services and trying to identify what your fair market value should be in terms of what you’re negotiating with a PI, your budget for industry sponsors, as well as what’s being paid out as part of your investigator compensation, you can look for opportunities to benchmark with your peers.”

Schick also suggests that clinical sites aim for RVU levels that are somewhere between Medicare reimbursement and the full charge for a given procedure or service within their own billing systems. “When I talk to sites about fair market value for medical procedures, I tell them [they] don’t want to be lower than Medicare, since nearly everyone is struggling at the margins with Medicare,” he says. “And you definitely don’t want to be above whatever the full charge is in your chargemaster. But anything between that I would argue is fair game since the payment levels from your commercial payers will vary quite a bit.”

Upcoming Events

-

07May

-

14May